Sculptor and internationally recognized medallic artist.

The Ancient Ones said that in the beginning man and Nature were one. Man was able to merge his consciousness with Nature, seeing it as an extension of himself. And in exploring it, he explored himself.

Walking through the forest, a man did not so much pause at a running stream, looking down at the water, as he immersed his own consciousness into the stream, traveling with it for miles to explore the layout of the land. A man wondering what a tree was like became a tree and let his own consciousness flow into the tree.

Man also “absorbed” an animal’s spirit before he killed it, so that the spirit of the animal merged with his own. In using the animal’s flesh, the hunter could draw on the animal’s strength. He took into his body the consciousness of all the things he consumed, and through his eyes, the beasts, vegetables, and birds perceived the dawn and sunlight as he did.

Over a period of time, when man lost his love and identification with Nature, he forgot how to identify with an image from its insides and so began to view it from its outside.

Through the eyes of sculptor Jeanne Stevens-Sollman ’68 there is no separation between Nature and other forms of life, nor Nature and spirituality. She believes spirit permeates everything.

“Nature is my religion,” she said. “I remember being about 10 years old, sitting in church, thinking, ‘These are good stories. I believe these things might have happened or that you needed them to happen in order to have strength. I believe you needed these people to get you from one day to the next. But I need a tree.’ I have felt it was always best when I felt troubled to sit outside. I still do.”

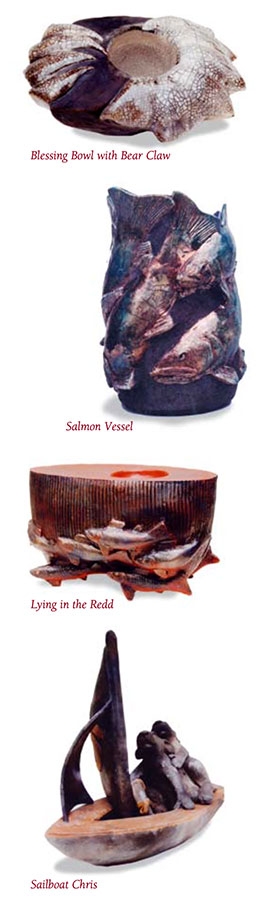

For the past 40 years, Jeanne has absorbed the natural world and translated what she has seen in ceramic and bronze sculpture and medallic art. The majority of her pieces are of animals. She sculpts them not as wildlife specimens, but as animated, spirit-filled beings.

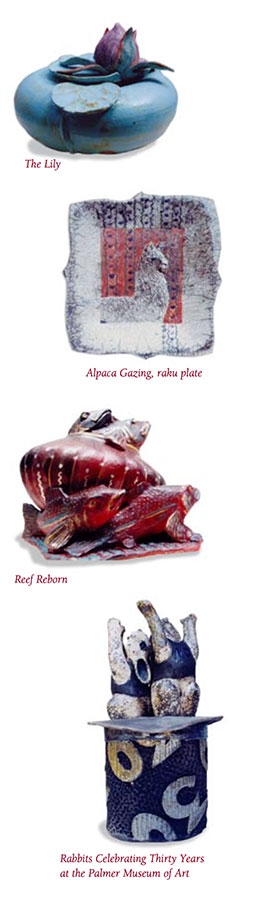

The animals that appear most often in Jeanne’s work are rabbits. Rabbits hold layers of significance for Jeanne. They’ve made fateful appearances in her life since early childhood. They’ve been as intimately tied to her success as being born with the hands of a sculptor. And rabbit has been a power animal (similar to a guardian angel) in her life.

Power animals are a part of Native American spirituality. Jeanne is hesitant about speaking of Native influences because lately these traditions have too often been commercialized. However, her great grandmother was a direct descendant of Massasoit, sachem of the Wampanoag nation. And like her Native ancestors, Jeanne believes that power animals act as our guide, our protector, our teacher, and our friend. They have naturally learned the lessons that we seek to understand, and they lend us the wisdom of their kind.

The lesson rabbit teaches (an animal who is often prey to other animals) is to move through fear and to use intuition when facing a challenging situation. Rabbit’s wisdom has guided Jeanne throughout her life.

Her path began on a rabbitry in Johnston. Her mother raised and tended the rabbits, and Jeanne’s job was to feed them. Her father carted the rabbits to her grandfather, and her grandfather skinned them. Income from the meat and pelts supplemented the family’s income.

The mud and muck of the farm became an Eden for Jeanne, a budding sculptor. “I’ve had this great affinity toward mud for as far back as I can remember,” she said. She particularly remembers the day a well was dug in the yard. A vein of clay was opened, begging to be molded.

During her childhood, her aunt, who was a potter as well as a shepherd, taught Jeanne pottery-making techniques. Jeanne also went on frequent trips with her aunt to the New Hampshire Potters’ Guild. On Saturdays, as a young girl, she attended art classes at the Rhode Island School of Design.

When Jeanne enrolled at RIC in 1964, Richard Kenyon, ceramics professor, became her mentor.

“I remember I had completed all my clay classes,” she said, “yet I was so obsessed with clay that Richard set it up where I could do an independent study with him. He would come up with these projects for me, like inventing and mixing glazes or building a kiln, and I’d be the only one in the room for hours. He gave me an extremely powerful foundation, and I am ever so grateful to him.”

Richard Kenyon also instilled in Jeanne the importance of creating a style of her own, a style unique to her.

“To be a potter is extremely competitive,” she said. “There are a lot of good potters out there. I thought that if I put little animals in relief on my pottery, or used them as handles, I could set myself apart.”

After graduating from RIC in 1968 with a degree in art education, Jeanne taught art at Bellingham High School in Massachusetts. In 1972 she graduated from The Pennsylvania State University with an MFA in ceramics. While teaching in Deer Isle, Maine, at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, she studied under New Hampshire Guild potter Jerry Williams.

Though Jeanne loved teaching at the School of Crafts, she found it took time away from her own work, and she was troubled. One day as she looked out over the ocean contemplating her life, Jerry came up behind her and asked what was troubling her.

Jerry deeply understood what it meant to be fearful and conflicted. The son of missionaries, Jerry had been a conscientious objector during World War II and had been imprisoned. On that day Jerry gave her a piece of advice which she lives by today. He told her to follow her heart.

Her heart told her to go with the clay. But it took major courage – rabbit courage – to make that leap. It meant going against the solid advice of her father to stay with teaching. It meant potentially “embarking on a career of poverty.”

But Jeanne was also a product of the ’60s. Like many young people, she embraced the alternative culture and radical views of the hippie movement. It wasn’t the LSD trips and love-ins that captured her imagination, but rather the rejection of the traditional 9-to-5 job, a life spent working for someone else at something you didn’t enjoy.

Carlos Castenada once wrote, “Look at every path closely and deliberately. … Then ask yourself, and yourself alone, one question: Does this path have a heart? If the path does, it is good. If not, it is of no use.”

Jeanne chose the path with heart. Today she is an internationally recognized artist whose work has been exhibited throughout the United States, Europe, and Japan. Her art can also be found in private collections and museums, including the British Museum, the Smithsonian Institute, the Warsaw Numismatic Museum, and the National Museum of History of the Ukraine.

When I met Jeanne, she exuded the peace of a person who has lived her dream. She is a tiny woman, no more than five feet tall, with skin as clear and rosy as a child’s. She parts her gray-brown hair down the middle, where it ripples in waves over her ears and is swept up in a bun in back. Her hands, like her features, are tiny and delicate. After a lifetime of immersing her hands in water and clay, the joints of her fingers appear slightly swollen, the fingers are slightly crooked, tapering off at the nails.

At the start of our interview, Jeanne laid a black portfolio on my desk, which I believed held photos of her work. Instead, she opened it up onto 8.5 x 11 photos of the unique architecture and furniture design of her husband Phil Sollman.

In almost every article and video clip published about her, Jeanne has cited the tremendous influence her husband has had on her life. Jeanne turned the portfolio toward me. Through round-rimmed glasses, she surveyed Phil’s work and indulgently explained it in detail. With grace and humility, she showed herself to be a woman who wears her power and accomplishments very lightly.

Phil is, indeed, a master craftsman. For almost 40 years he has designed and constructed architecture and wood furni- ture for a wide range of clientele. He also designed and built their home in rural Centre County, Pennsylvania. It has an earthy interior, replete with flagstone floors and leaded-glass windows. When they purchased the land in 1976, Phil saved up materials to build as he could afford it, which meant that they never had to pay a mortgage. Today, they live isolated in the middle of 11 acres. Beyond that are miles of farmland.

“Nature is a very dominant, aesthetic presence around the house,” said Phil in a phone interview, “and it inspires me as much as Jeanne. It’s hard to find any facet of our life that isn’t influenced by Nature.”

Phil’s design style can best be described in the language of Frank Lloyd Wright as “free form/organic,” reflecting the forms found in Nature. He spends painstaking long hours bending wood (the natural world contains very few straight planes).

Phil and Jeanne each work in their own separate studio, Jeanne upstairs, Phil downstairs. In the afternoon they come together to eat lunch and take a walk with the dogs. When they’re stuck on a project, they confer with each other. Afterwards they go back to work, quitting at four.

Jeanne met Phil in 1970 during her second semester at Penn State. Phil was in his last year, completing a degree in architecture. In ’76, when Jeanne left teaching, Phil had also closed his construction business. Through the winter the young couple rented quarters in an old farmhouse and survived on squash from their garden. Phil designed and made furniture, and Jeanne made pottery.

Jeanne remembered customers dropping by the farmhouse to place an order (usually for ceramic cereal bowls or casserole pots). “That meant $30 or $40 in groceries,” she said.

In 1976 she read the novel Watership Down by Richard Adams, an allegorical tale entirely populated by rabbits. “By humanizing rabbits,” Jeanne said, “Adams gave me permission to humanize them in clay.” After reading his novel, Jeanne’s rabbits, once confined to the lids of casserole pots, became individual sculptures. In the same year the first gallery, Toadflax, Inc., became interested in her work.

“The gallery owner would come by my little funky studio,” she said. “I had an annex out in the chicken coop where I stored the sculpture. Chickens would be walking around our feet, clucking. But no matter what kind of rabbit I made for him, he sold it. I was just cranking them out.

“In the beginning the rabbits were selling for $6 each. Then one day I said to Phil, Why don’t I see if I can sell them for $10? And then later I thought, maybe I can get $12 for them. Will people want to pay $12 for this miserable little rabbit?”

Jeanne broke into a lovely peal of laughter at the thought of her early rabbits. “In the beginning, she said, “they were these nasty maniacal-looking things. They were just mean looking. It took time for them to arrive in the shape they’re in now.”

Jeanne’s rabbits dance, sleep, frolic, and dress up as clowns. “I continue to make them because people enjoy them,” she said.

Ten years later, Jeanne got involved in medallic art (the art of making medals) as a way to enhance her sculpture. In 1987 she received her first commission from The Pennsylvania State University to design the Barco Medal. Many other commissions followed. She designed Iowa’s State University’s first-ever Presidential Mace and Collar and Penn State’s Alumni Achievement Medal, Alumni Fellow Medal, and Institute of Arts and Humanities (IAH) Medal. Pianist Emanuel Ax, violinist Itzhak Perlman, and cellist Yo-Yo Ma were recipients of the IAH medal in March 2009.

International acclaim for Jeanne’s work poured in. In 1998 Jeanne earned the top award for medallic art in The Hague, Netherlands. In 1999 she received the J. Sanford Saltus Award for Signal Achievement in the Art of the Medal from the American Numismatic Society. In 2007 she became a Penn State Alumni Fellow for outstanding achievement in her field, and the Numismatic Association honored her with the Award of Excellence in Medallic Sculpture, one of the highest medallic awards in the world.

Between designing medals and producing rabbits, Jeanne began creating life-size sculptures of animals in bronze. A recent commission was to design wolves for the entrance to Penns Cave, a water cabin and animal reserve. With every commissioned piece, Jeanne brings her own world view.

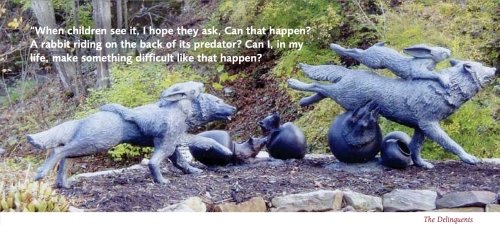

For this commission she created two rabbits riding the backs of two juvenile wolves, while three adult wolves look on as if to say, “That’s not quite right.”

“When children see it, I hope they ask, Can that happen? A rabbit riding on the back of its predator? Can I, in my life, make something difficult like that happen? Do I have enough power to make that happen?”

Throughout Jeanne’s life, extraordinary events have happened, and often an animal has figured in the event. Jeanne’s parents noticed early on that animals seemed drawn to her. Phil, too, has witnessed unusual animal occurrences with Jeanne. He said, “She’s got some kind of magic thing going on with animals. Probably the same thing that attracted me to her.”

Jeanne laughed, but with a twinkle of knowing in her eyes. Perhaps after a lifetime of learning to understand the messages offered in the natural world, animals intuitively sense her respect for them. The respect, however, is mutual, for Jeanne has found animals to be her greatest teachers.

Around 1980, after she and Phil had moved into their unfinished house, Jeanne became a shepherd of six ewes and a ram. In 24 years as a shepherd, she only needed to call the vet twice regarding a sick animal. On every other occasion she was able to use her own knowledge of herbs to treat and heal the animal.

“Often it comes down to instincts, intuition,” she said. She also found that by observing animals in Nature, she could understand the medicinal effects of particular plants. Animals seem to intuitively know which plant to eat or rub against when they’re ill or wounded.

Before leaving to visit her father, Jeanne left me the gift of a handcrafted ceramic tray with her signature rabbit poised at the center, a way of saying thank you.

When I asked her if she had any plans for the future, she said she has never had a “next,” only a “now.” “It’s the only place where happiness exists.”

If you live long enough in the world you can lose the magical approach to life, placing limitations on what is possible. There have been countless extraordinary events in Jeanne’s life because she kept that magical state of being, that wonder of being alive, that oneness with all other life forms. The Ancient Ones said we were once such creatures in the beginning.